Mental Health & EBSA

Home » Parents & Carers » Mental Health & EBSA

What is Mental Health?

We all have mental health, just as we all have physical health. Our mental health is how we’re feeling inside, or how we are emotionally. It’s a bit like internal weather.

Mental health includes our emotional, psychological, and social well-being. It affects how we think, feel, and act. It also helps determine how we handle stress, relate to others, and make healthy choices.

Our mental health is as important as our physical health, as it affects our daily lives. i.e. how we feel, impacts on our ability do the things we need and want to, including work, study, getting on with people and looking after ourselves and others.

Can mental health difficulties be considered a disability?

Some children suffering with mental health problems can be considered disabled under the Equality Act 2010. All schools are under an obligation not to discriminate against pupils on the grounds of disability.

Under the Act, disability includes a mental impairment. The mental impairment must have a substantial and long-term adverse effect on the person’s ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities.

Long term means that the symptoms have lasted or are expected to last for 12 months but this need not be consecutive. Transient symptoms may not fall within the Act.

The term ‘disabled’ in the Children and Families Act is the same as the term used in the Equality Act 2010 – It is defined as:

- The child has “a physical or mental impairment which has a substantial (i.e. more than small or insignificant) and long-term (lasted more than 12 months) adverse effect on his ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities.

- The inability to attend school is a “normal day to day activity”.

Equality Act 2010

If a child or young person falls within the definition of disability above then the school has particular obligations. Schools are under a duty to make reasonable adjustments to put disabled students on a more equal footing with pupils without disabilities.

If an adjustment is reasonable then it should be made and there can be no justification for why it is not made. An adjustment may be considered unreasonable if it is very expensive and may be a reason for a school refusing to offer school-based counselling.

The duty to make reasonable adjustments is also anticipatory. This means that schools should give thought in advance to what disabled children and young people might require and what adjustments might be needed to prevent disabled students from being disadvantaged.

The following are examples of mental health symptoms that can be regarded as a mental impairment under the Act:

Anxiety, low mood, panic attacks, phobias, eating disorders, bipolar affective disorders, obsessive compulsive disorders, personality disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, some self-harming behaviour, depression, schizophrenia.

Care, education and treatment reviews (CETR)

A CETR is a meeting about a child or young person who:

- has a learning disability and / or autism

- is at risk of being admitted to hospital

- is in hospital

A CETR meeting should happen before any decisions are made about whether hospital care is right. This looks at why your child might need to go into hospital and whether extra support can be given at home instead.

This information gives a brief overview of the CETR programme (Care, Education and Treatment Review) which NHS England provides.

A CETR meeting brings together:

- the child/young person and their family

- people who commission and provide services (e.g. nurses, social workers, commissioners and other health, education and social care professionals)

- an independent clinical adviser

- an expert adviser who will be someone with lived experience of having a learning disability or autism or a family carer

At the CETR meeting, they seek the views and experience of the family and carers and the young person themselves to make sure that all options have been exhausted when it comes to supporting the young person to remain in their local community.

They also seek to understand how local services are able to support the young person and identify any barriers to accessing that provision. They make suggestions as to any other options or opportunities which could help the young person live and thrive in the community.

A ‘Key Lines of Enquiry’ form will be completed in this meeting. This helps put together a summary and feedback for the child or young person.

Requests for CETRs are usually made through the professional team but can be requested directly by a person or their family where needed.

Find more information, advice and support from NHS England.

Emotional based school avoidance (EBSA)

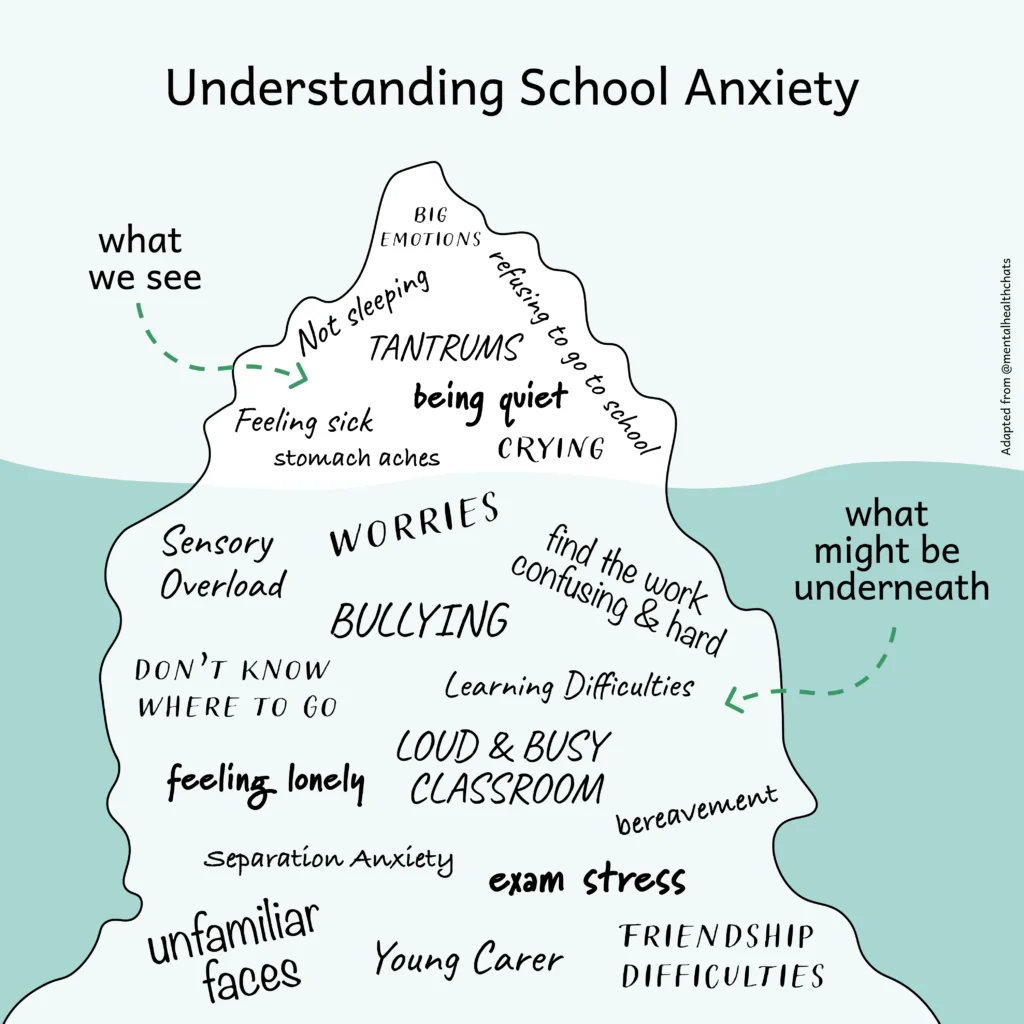

Emotionally Based School Avoidance (EBSA) refers to a child or adolescent who has difficulty attending school. The attendance at school creates uncomfortable emotions such as stress and anxiety and this can cause both physical and emotional symptoms.

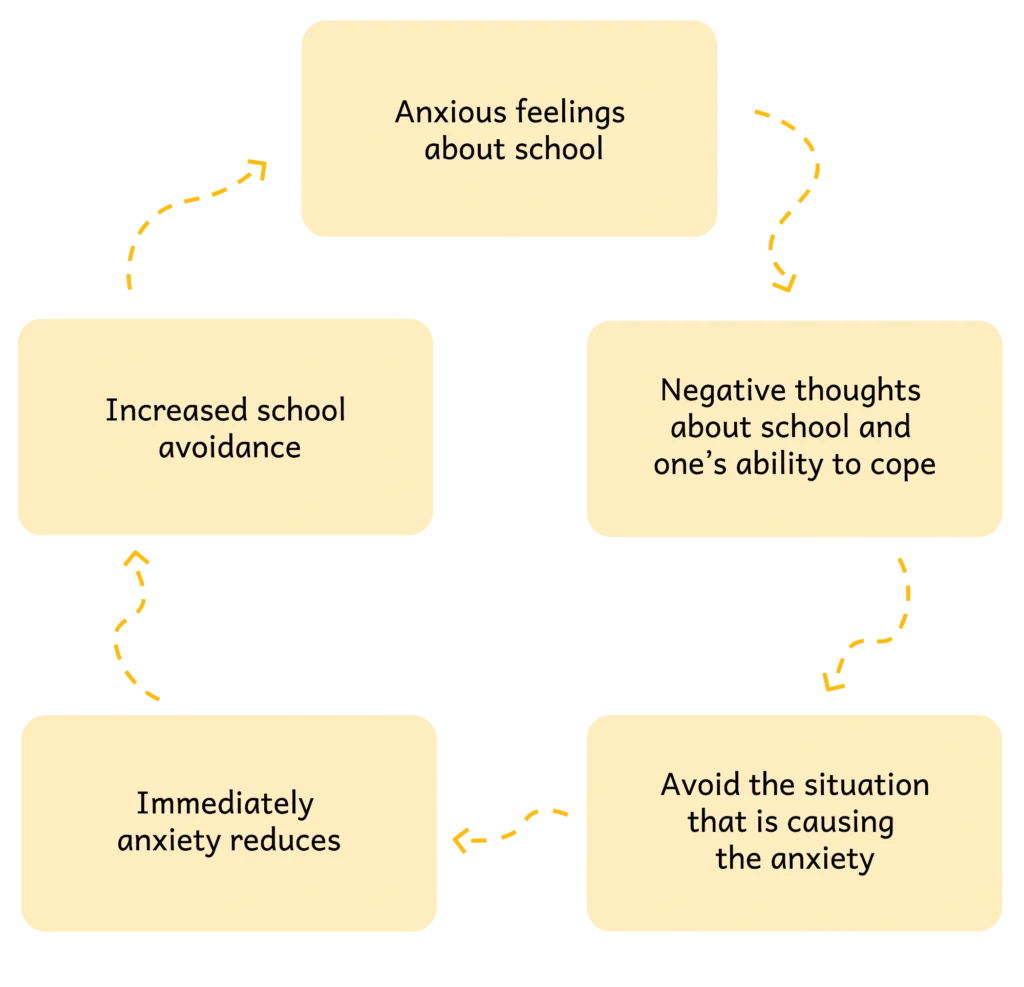

The difficulty with Emotionally Based School Avoidance is that avoiding school escalates the feelings of anxiety, and this can further exasperate school refusal and lowered attendance.

Emotionally Based School Avoidance is not the same as truancy, and needs to be carefully, compassionately and considerately managed to work WITH the child and their family.

When a child experiences emotionally based school avoidance, they experience high levels of negative emotions surrounding school, this can include:

- Anxiety

- Fear

- Panic

- Negative thoughts

- Catastrophising

- Physical symptoms such as nausea

The symptoms that a child feels are very real for them, and are both emotional and physical, they can be extremely distressing. Avoidance is used to reduce the anxiety, it is a natural response to the discomfort, whereby, the brain attempts to move us to safety. However, when the child needs to return to school, the feelings of anxiety increase further and this creates a distressing cycle for the child which becomes difficult to manage.

Signs of EBSA

- Fearfulness, anxiety, tantrums or expression of negative feelings, when faced with the prospect of attending school.

- Complaining that they have abdominal pain, headache, and sore throat, often with no signs of actual physical illness.

- Complaining of a racing heart, shaking, sweating, difficulty breathing, butterflies in the tummy or nausea, pins and needles and other physical signs they might be anxious.

What should you do?

One of the most important ways you can support your child is to calmly listen to them and acknowledge that their fears are real to them. Remind them how important it is to attend school and reassure them that you and the school will work with them to make school a happier place for them.

Let the school know there is a problem as soon as possible and work in partnership with the school to address the issue. A plan should be made with the school to help your child. When you start to put the plan in place, your child may appear unhappy and you should be prepared for this. It is really important that all adults both at home and school work together to agree a firm and consistent approach, and a positive ‘united front’ is recommended. Concerns about the plan should not be shared with your child.

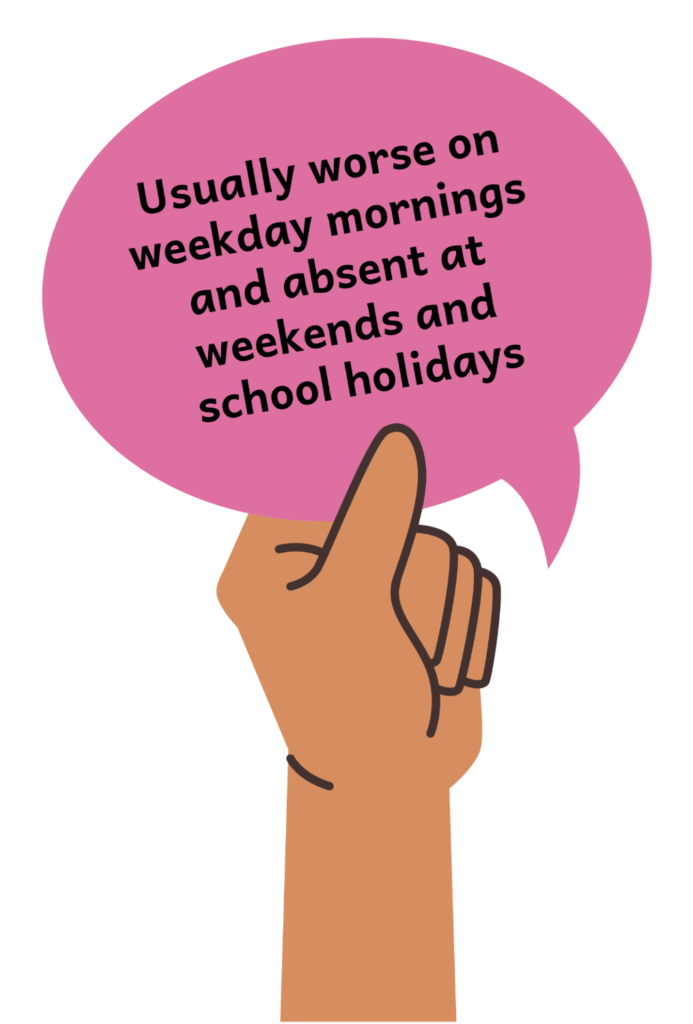

It should be anticipated that there may be difficulties implementing the plan and when this happens solutions should be found. Try to be optimistic – if your child does not attend school one day, start again the next day. Remember that it is likely to be more difficult after the weekend, a school holiday or a period of illness.

You may be tempted to change schools, however, research indicates that often difficulties will re-emerge in a new school. Therefore, wherever possible, it is better to resolve the issue in your child’s current school.

Finally, it is very important that throughout your child has someone to talk to. This could be a family member, friend, someone in school or an organisation.

What should school do?

- Listen to you and your child and acknowledge the difficulties faced by your child and you as a parent/carer.

- Keep in touch with you and your child even during extended periods of non-attendance.

- Work in partnership with you and your child to find ways of overcoming any difficulties so as to improve your child’s attendance.

- Work together to develop a plan to support your child back into school.

- Meet with school regularly to review the plan, celebrating the progress made and making modifications to the plan if needed.

Consider the support your child might need when they arrive at school. This might include:

- Meeting a friend or key adult.

- Going to a quiet space to settle before school starts.

- Having responsibility e.g. a monitor role.